This project, which is a spinoff of my blog

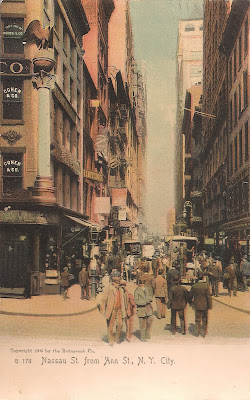

Dreamers Rise, is intended to present a focused selection from the many thousands of scenic images produced by the Rotograph Co. of New York, NY in its short history (c.1904-1911), a period that corresponded to the height of the early 20th-century American postcard boom. These images, the vast majority of which were produced in Germany (German manufacturers were at the leading edge of photographic and printing technology), captured a wide variety of scenes, ranging from skyscrapers to slums, from country churches and schoolhouses to seaside resorts. Since the technology for the mass-reproduction of true color photographs was in its infancy, many of the cards were hand-colored or treated with various processes to add layers of color. While other important card manufacturers, some of which lasted far longer, were active at the same time, at their best the Rotograph cards stand out for technological and artistic excellence as well as for their comprehensiveness in subject matter.

The guiding principles of this project are three propositions:

1) That these images, which originated as photographs, have documentary value based on the buildings, streets, parks, beaches, and other public and private spaces which they depict. This shouldn't be taken too far; many of these images, or similar ones, have been reproduced elsewhere, and there may be little specific information in them that is not already amply documented. Nevertheless, even bearing in mind the highly subjective (and no doubt largely market-driven) process of determining which scenes would be chosen for portrayal, the images provide, even if unintentionally so, useful cumulative evidence about the physical appearance of the United States a century ago that may be unfamiliar to many viewers.

2) That the manner in which, in much of Rotograph's production, black-and-white photographic originals were transformed into colored view cards added an extra dimension which transforms the results into something more aesthetically complex. They are, in effect, hybrid images, partly documentary photos, partly paintings (or prints of paintings), and the resulting ambiguity of their status not only opens up additional possibilities for their interpretation but anticipates certain movements in contemporary art and photography. (For more on this argument, see my post "

Two More Bowery Views" at Dreamers Rise.)

3) That an examination of the ways in which these postcards were created, mass-produced, marketed, and distributed may provide interesting insights into aspects of early 20th-century American society, in particular in regard to such themes as urbanization, the spread of leisure activities and consumerism, and developments in transportation, commerce, and the mass media. In addition, the inscriptions and addresses and identities of the senders and recipients may cast light on daily life and personal relationships. I'm not a professional historian (or even an amateur one), so my aim will be more to provide food for thought than to defend any particular thesis.

In spite of its short lifespan, the Rotograph Co. produced tens of thousands of images (one estimate its 60,000). Many were not scenic view cards and thus lie outside the scope of this project, but even among the view cards I have no interest in being comprehensive. Instead, I would like to focus on certain locations and specific themes, as well as, to a lesser extent and when information is available, on the history and operation of the company and its relation to the American marketplace. My intention is to organize these images into a series of thematic posts that will serve as virtual "rooms."

I want to make it clear that I am not an expert on the Rotograph Co. or on any of the themes alluded to above. Although there appears to be no published volume devoted solely to the Rotograph Co., whose corporate history consequently remains poorly documented and somewhat mysterious, there are several useful resources for those seeking more authoritative information. The best place to start is probably the website of

the Metropolitan Postcard Collector's Club, which is not only an indispensable source for the study of postcards in general but also has extensive material about the Rotograph Co. and its production methods in particular.

A periodical called the

Rotograph Review was issued beginning in 1977, but I've been unable to track down an archive of the numbers that appeared before it ceased publication. There is a rather nice YouTube video montage of Rotograph view cards of New York City, entitled

Wish You Were Here. A web project by the Queens College School of Library Science,

Postcards from the New York Waterways: 1898-1923 (link no longer functions), has many Rotographs and is a model of intelligent online presentation. Daniel Gifford's doctoral thesis,

To You and Your Kin: Holiday Images from America's Postcard Phenomenon 1907-1910, though not directly related to the history of the Rotograph Co., is an excellent source of general information on the early 20th-century postcard boom; a

PDF of the thesis is available online.