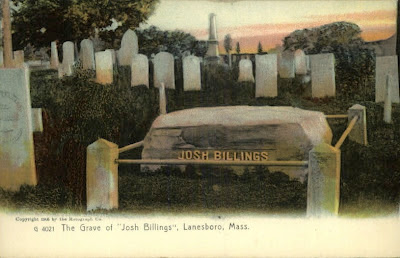

Sometimes the most unpromising artifacts turn out to be the ones with the weirdest stories attached to them, and the postcard above is a prime example. I imagine that the name Josh Billings will draw as much of a blank with most people today as it did with me, but two things could be immediately deduced from the caption: that he was once a person of some renown, and that he wasn't really named "Josh Billings." In fact, "Billings" was born Henry Wheeler Shaw in Lanesboro, Massachusetts in 1818. He came from a distinguished political family but after a checkered career settled into journalism, a profession at which he became successful enough that he was photographed in the company of two pseudonymous peers, one a certain Petroleum V. Nasby, now largely forgotten, the other a man who went by the name of Twain. He was known for his pithy "witticisms," many of them in dialect, one of which ("I don't rekoleckt now ov ever hearing ov two dogs fiteing unless thare waz a man or two around") turned out to be singularly unfortunate, given what is reputed to be Shaw's eventual fate.

Shaw died in 1885 in Monterey, California, and as the postcard below indicates, was interred near his birthplace. At least most of him was.

According to a bit of Monterey lore that John Steinbeck worked into Cannery Row, when Shaw died, the local doctor, who apparently also served as an undertaker, removed some of his internal organs during the embalming process and unceremoniously flung the tripas into a nearby gulch, where they were discovered a boy looking for fishbait -- and by his dog, whom Steinbeck describes as dragging "yards of intestines on the ends of which a stomach dangled."

When some of the local citizens heard of this discovery, and simultaneously learned of the death of "Josh Billings" at the nearby Hotel del Monte, they quickly put two and two together and hastily summoned the doctor.

They made him dress quickly then and they hurried down to the beach. If the little boy had gone quickly about his business, it would have been too late. He was just getting into a boat when the committee arrived. The intestine was in the sand where the dog had abandoned it.What Steinbeck's source for this gruesome incident was, and whether there was any truth in it, I don't know (it recalls a similar, and also possibly apocryphal, story about Thomas Hardy's heart and a cat), but true or not I suspect that Steinbeck's retelling of it has probably done more to preserve the name of Josh Billings than anything the latter ever penned.

Then the French doctor was made to collect the parts. He was forced to wash them reverently and pick out as much sand as possible. The doctor himself had to stand the expense of the leaden box which went into the coffin of Josh Billings. For Monterey was not a town to let dishonor come to a literary man.

"Hillcrest," Shaw's birthplace, was operated as an inn for a period during the first half of the 20th century. I haven't been able to find out whether it still stands and if so whether it is still regarded as a local landmark.